Cult Survivor Empowers Other Victims Breaking Free of Coercive Control

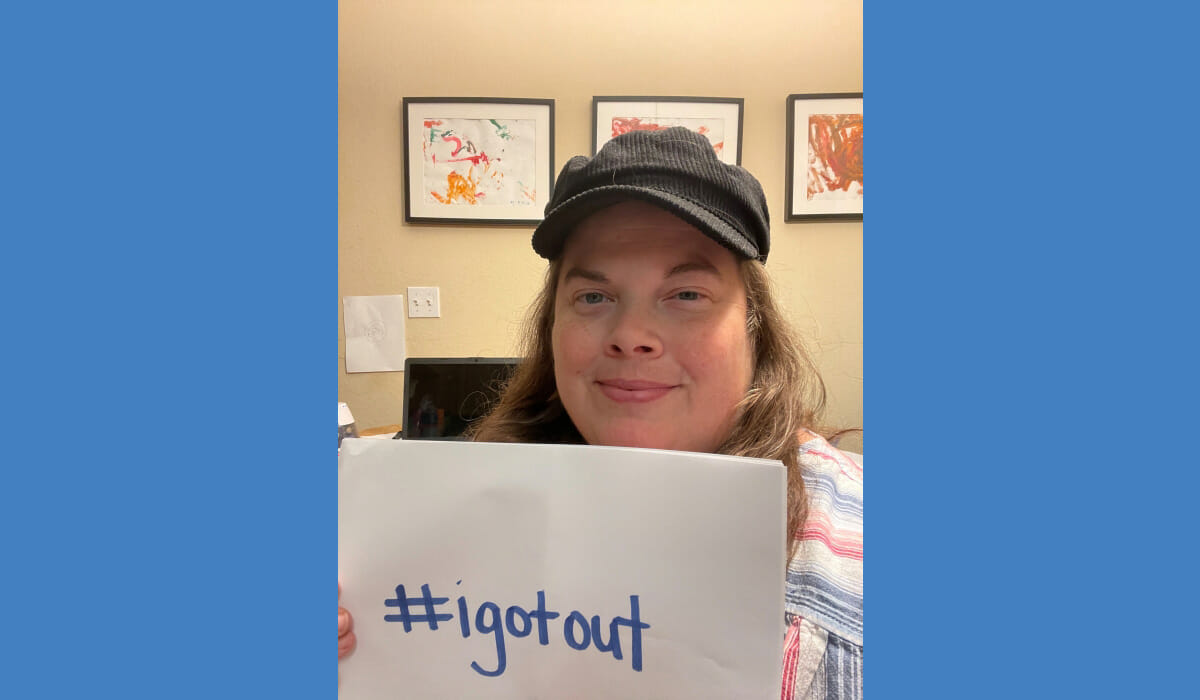

Meet Daily Point of Light Award honoree Tabby Chapman. April is Global Volunteer Month, a global movement to recognize volunteers and people who actively support their communities, whether through volunteerism or other elements around the Points of Light Civic Circle®, like Tabby. Read her story, and join the Global Volunteer Month celebration.

Content Warning: Points of Light is proud to share the following uplifting and inspiring story. However, we acknowledge that a small portion below may be difficult for some readers. We encourage you to please care for your own wellbeing above all.

Tabby Chapman has seven-year-old twin boys, both on the autism spectrum, taking care of whom she considers her day job. As a California family they spend time relaxing at the beach, but they also enjoy playing Legos and video games. Tabby’s career is as a marriage and family therapist and a professional clinical counselor. She’s currently working on her PhD in forensic psychology, public policy and law with the intention of redefining the legal concept of coercive control.

Unbeknownst to many, Tabby was a member of the infamous NXIVM cult for several years until her escape in 2014 when she used lack of finances as a way to get out without attracting litigious attention from leadership as many ex-members did. NXIVM started as a personal development company using a multi-level marketing scheme by Keith Raniere and ended with him going to prison for sex trafficking—among other crimes. Now, Tabby is taking a difficult period of her life and turning it into a force for good with her nonprofit, The Freedom Train Project, through which she helps people get away and recover from cults and coercive control.

The idea initially came to her while filming the documentary miniseries Seduced: Inside the NXIVM Cult alongside other Raniere victims and cult experts in 2018. Even after the investigation, arrests and negative press, some NXIVM members remained dedicated, and victims were discussing possible reasons behind the phenomenon. So, in 2020, without any philanthropic grants or government funding, Tabby and her team became the assistance Tabby would have liked to have had during her days with NXIVM.

What inspires you to volunteer?

I was victim of a cult myself. They used financial abuse towards me, so I didn’t have money to leave. I eventually left with maybe $900 and a lot of debt, but I think with a victim outreach agency I would have been able to get out faster. There really isn’t a space for cult victims in victim advocacy, so what we’re doing at the Freedom Train Project is unique.

Describe your volunteer role with The Freedom Train Project.

As a victim advocate, I reach back out to the people who contact us with a cry for help. An intake form helps me rule out someone who’s having a mental health crisis versus someone who’s in a cultic environment or experiencing coercive control. After the intake, I do an interview and provide referrals and resources for help in either situation.

Most people in cultic environments call me when they’ve left and are looking for therapists who are friendly towards cult victims. Cults will often tell members that therapists, doctors and law enforcement are out to hurt them. There are also therapists who believe that cult victims are not coerced. Or, unknowingly, they will use the same verbiage or vernacular that people in the cult used, so it’s very traumatizing. A lot of cults will repurpose psychological language as part of their manipulation tools.

As executive director, I also run the rest of the organization – from program support for victims to creating buzz around the mission and organization. I create partnerships with shelters, therapists, medical facilities and more to have expedited support for clients. I’m working on submitting a policy change request to Congress to expand the Victims of Crime Act to include coercive control as a specific victimization to enable organizations like mine to receive grants to help victims.

How would you define coercive control?

In California, coercive control is defined as part of domestic violence. The goal is to get it separated out on its own, because coercive control can be used in any situation. Even a car salesman can use it. The broadest definition is using manipulative tactics to get someone to do something against their will. It can be anything: financial, verbal, mental or emotional abuse. Anything that is not physical abuse.

Do you mainly work with people in Southern California?

So far, I’ve only had one or two Southern California clients; I do more national work. There are only two or three states that have laws against coercive control in domestic violence. There are one or two states where there are laws against coercive control, but they’re not often upheld. And if there are no laws against whatever’s happening to victims, it’s a lot harder for them to get the help they need.

Another challenge is the high number of male victims who need help. Domestic violence can happen to anyone, but it’s often women. As a result, there aren’t a lot of places that can help men, like homeless shelters. I utilize the shelters as a resource, so when I have a male victim who’s calling me, that can be challenging.

Do you have other volunteers?

We have an amazing board of directors who are all professionals in victim related fields including doctors, therapists, housing specialists and public policy experts. They make mission-level decisions and support the work being done. Including myself, we have three victim advocates, one of whom specializes in domestic violence and the other in sexual assault.

What’s been the most rewarding part of your work?

It’s getting the phone calls. I didn’t know how it would go, and we’re not doing a lot of advertising. Another documentary that I was in just came out, and many people are looking me up from that. Seeing that we’re being effective without any kind of budget is great. Ultimately, my goal is to run a whole team and become a research institution for cultic and coercive control.

What have you learned through your experiences as a volunteer?

As the executive director, I’ve learned everything. I’ve never done that before. As a victim advocate, I’ve learned that sometimes people know they need help, but they’re not quite ready for it. I can’t push my agenda on them. They might not believe they’re in a cult, but what they’ve read on my website strikes a chord. And they’re usually a bit scared.

Why is it important for others to get involved in causes they care about?

Coming from my psychology background, I feel like there’s a lot of evidence that shows that working with causes that are bigger and outside of ourselves causes us to feel connected to a sense of community, which increases our sense of efficacy in the world and belief in ourselves. There is nothing but benefits to volunteer service, especially for someone with low self-esteem or who has experienced abuse. They can often grow through areas they’re stuck in as they’re healing from abuse simply by helping others in similar situations.

What do you want people to learn from your story?

If you have an idea, start building it one step at a time. And always keep your mission in mind. If everything you do for your organization points towards that, you’ll get there faster. If there are any agencies interested, we’re happy to speak with people about what we’ve done and how we can help them expand to work with cult victims or create their own agency.

Join the Global Volunteer Month celebration! Download our Global Volunteer Month toolkits and access resources to encourage volunteerism and civic action, recognize volunteers, and raise awareness for your organization’s needs and funding opportunities.