A Child of Jim Crow Laws, Senior Citizen Promotes Education as Global Volunteer for Peace Corps

Meet Daily Point of Light Award honoree Lincoln Law. Read his story and nominate an outstanding volunteer or family as a Daily Point of Light.

82-year-old Lincoln Law remembers the day that then President John F. Kennedy announced the creation of the Peace Corps. Signing an executive order on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy established the volunteer organization to combat negative stereotypes of Americans, particularly in post-colonial Africa and Asia.

“(Kennedy) announced (the creation of the Peace Corps) on the TV. He talked about how people could go and help people around the world. I thought that was the best idea that anybody could have, and the idea stuck with me, so when I retired, I decided I’d do it.”

As a young man, Lincoln first served as a seaman on two U.S. Naval ships that both sailed around the world, the Navy racially integrating just a few years prior, and then worked for the Los Angeles County school system. When it came to volunteering, the San Pedro, California resident combined his ambition to see the world and his dedication to giving back to the community.

“I joined the Navy because I wanted to go places and see what was going on in the rest of the world,” Lincoln says. On giving back? He says it’s simple. “It’s a good idea. It’s just natural to me. My mother and father always said that you should really do the best you can. Look, we’re stuck on this planet, all of us, and if we don’t help each other who’s going to help us?”

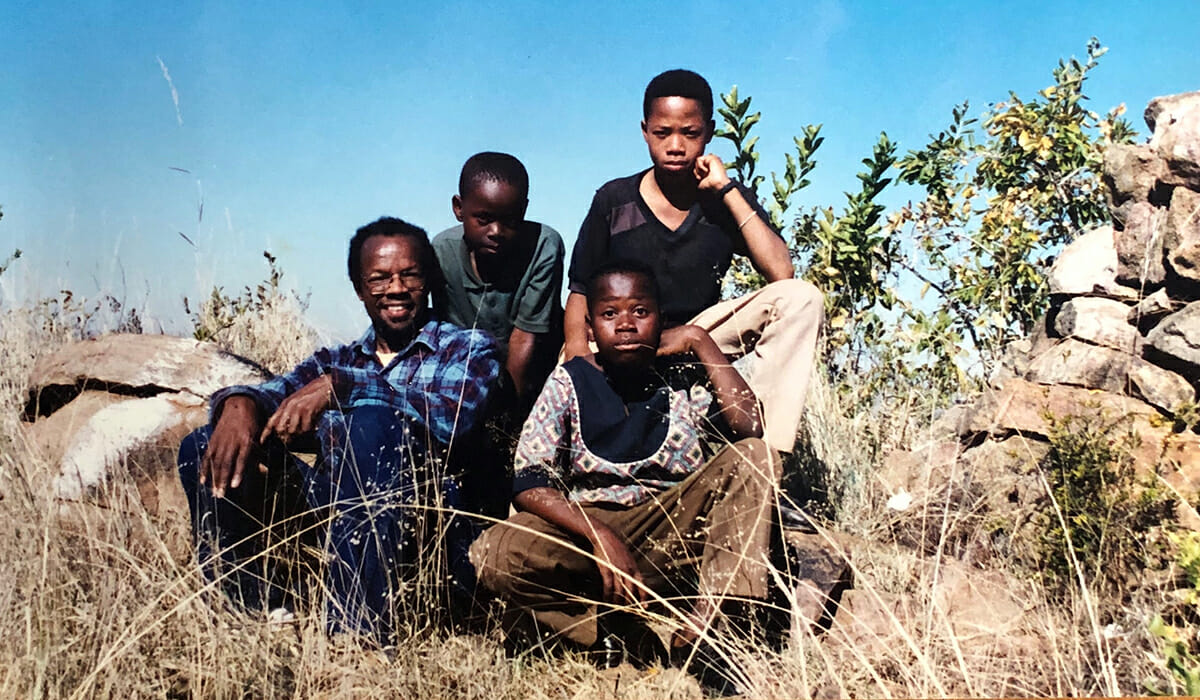

In 1992, when Lincoln retired from his career with the county, he applied to be a Peace Corps volunteer in the Solomon Islands at age 56. He then signed up to serve in South Africa from 1997 to 1999, shortly after the country ended apartheid. Lincoln completed his most recent Peace Corps tour in Tanzania, where he helped the community create a functioning library. Volunteering as a teacher and teacher trainer, Lincoln was particularly proud as an African-American to answer the call to serve in South Africa.

“Before going to South Africa, I was an activist for the elimination of apartheid. The Jim Crow we felt here in America and the apartheid system, they’re not really that much different. I consider them both the same but just on different plots of land.”

Observing the black South Africans he was volunteering with, just a few years out from the end of apartheid, Lincoln says he was shocked by their lack of confidence in their own chosen professions.

“You could actually see the effect that apartheid had left on the people there. The teachers had hardly any self-esteem. It’s kind of hard to teach others if you don’t have any self-esteem yourself. The lack of confidence, hesitation, if they had a thought, they were afraid to act on it. Coming from America, it seemed like a different world.”

Teachers had not been allowed to express their creativity while under apartheid, and Lincoln says reteaching the group, newly freed from the ravages of the apartheid education system, was a high point for his service. His impact on other communities has yielded additional long-term effects, says Tanzania Peace Corps county director Nelson Cronyn, Ph.D. By helping the Tanzanian community leverage external resources to build and stock a library, and assisting teachers in the community with their skills, Nelson says that Lincoln brought people together to address problems through collective action.

“By demonstrating the power of one dedicated individual to elicit positive change; Lincoln fostered a very positive impression and understanding of Americans by living at the same level as his Tanzanian colleagues,” Nelson says, “contributing to the solution of pressing community problems, and sharing their everyday lives on a long-term basis – thereby fulfilling the Peace Corps’ mission.”

During his three years in Tanzania, Lincoln taught math at the secondary school level, helped to build a water catchment system for the community and collected 22,000 books for the newly built library. According to Lincoln, the community had never before had access to public books.

“The community didn’t have a library. The books they had were locked in a room, they weren’t accessible to students. If one child is able to use the library and learn to read, that means they will be able to teach someone else to do the same. It’s a domino effect.”

His impact is a model for people of all demographics, says Nelson, and service that will continue to inspire others.

“Perhaps the biggest impact Lincoln had with his volunteerism was demonstrating that anyone – regardless of color, background, or age – can contribute in substantive ways to the greater good by volunteering,” Nelson says. “He models positivity and perseverance, characteristics that are requisites for solving challenging problems faced by the human enterprise.”

Lincoln hopes to continue volunteering in other communities for the Peace Corps, and is raising funds to expand the library he helped to build in Tanzania. While currently stateside, Lincoln is a volunteer at the African American Firefighter Museum in Los Angeles, which promotes information about the heritage of African American firefighters in the U.S., once restricted and segregated from white firefighters.

Lincoln says his volunteerism continues to come full circle even today, recently receiving a Facebook message from a grown man who’d been taught by Lincoln decades before in the Solomon Islands.

“He let me know how much of a difference that the experience he had in school made on his life. He went on to college, and he became a professor himself at the college on Solomon Islands. Now that’s the most inspiring and unexpected action that I’ve had…It was so much more rewarding to hear after 20 years, you did make a little difference.”

Do you want to make a difference in your community like Lincoln Law? Find local volunteer opportunities.