Laughter is the Best Medicine: Improv Comedian Performs for Hospitalized Children

Hope England found her calling as a tireless volunteer who brings cheer and the healing power of laughter to seriously ill children in a funny way. An aspiring actress and comic, England moved from her native Tennessee to Chicago to train for three years with the renowned Second City comedy organization, which has trained many famous comedians, from John Belushi to Tina Fey to Steve Carell. In England’s case, however, an audition in Los Angeles for NBC proved disappointing.

England says she’s now found a more rewarding path for her talents. Her heart aches for children and teens whose own life-changing disappointments involve serious injuries or illness. For England, improvisational-style comedy is a very serious way for her to help them.

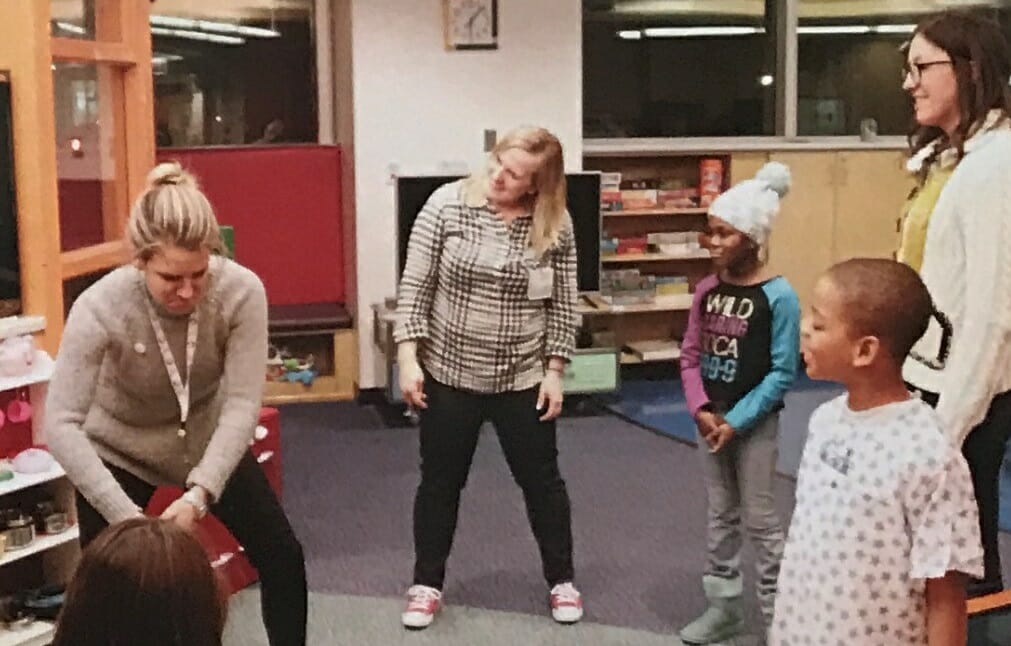

England created Humor for Hope to bring the gift of laughter to Comer Children’s Hospital in Chicago. She and other professionally trained comedic actors donate their time and talents several days a week.

“Once we can connect with the kids through laughter, it really opens up a place for us to go much deeper,” she says. “If they can start telling us, ‘I’m really sick’ or ‘It makes me sad that I lost my leg,’ that can open the door for doctors, nurses, and mental health professionals to better understand and treat the child’s emotional needs.”

England also uses her compassion and interpersonal skills as a full-time trauma intervention specialist, working in Chicago’s toughest neighborhoods with young victims of gun violence. She ends up seeing some of them at Comer, including a 3-year-old boy left paralyzed by a gunshot.

Many patients at Comer Children’s Hospital come from disadvantaged homes. The hospital, operated by the University of Chicago, is on the city’s impoverished south side. Whether they’re there because of illness, injury, crime, or abuse, Comer’s young patients might not have much support from their families, and all are experiencing pain and fright.

“A crucial piece is the context in which this program is happening,” says Dr. Lisa McQueen, an emergency medicine specialist at Comer.

McQueen has observed that children’s hospitals often see resources directed to younger kids. “It’s easy to convince people to give money to a bald 6-year-old with cancer; there’s not a lot of people who reach into their wallets for a 15-year-old boy who is perceived to belong to a gang,” she says.

McQueen says Humor for Hope is different in that it reaches out to all patients, including teens injured by violence.

Humor for Hope volunteer Katie Tyner says she feels especially good when humor helps a jaded, tough-skinned teen relax. McQueen notes that older kids relate better to comedy routines than to music therapy or other activities they believe they’ve outgrown.

Equally important is Humor for Hope’s positive effect on physicians, says McQueen, who also heads the hospital’s pediatric residency program: “A reality of training in a program like ours is seeing really horrible things, which can lead to doctor burnout.”

Last year, she invited Humor for Hope to a professional retreat, where young doctors participated in improv sessions to discuss their emotions. “It was the highest-rated workshop we’ve ever had,” she said.

Jessica Antes, another alumna of Second City who volunteers with Humor for Hope, says practicing improvisation teaches doctors “compassionate listening.”

“In improv, there’s no script. Participants must listen closely to every word instead of waiting to reply with memorized lines,” says Antes. “In a medical situation, it means giving each patient and family your undivided attention. You may know what their diagnosis is, but for them, this is the first time they’re going through it.”

England’s unique idea of using improv as “medicine” has proven cost-effective, portable, and adaptable to individual patients. “You don’t need any props,” she says, “and it’s a great way to use your imagination for the ones who aren’t mobile or can’t get out of their beds or who are hooked up to machines.”

“With improv, even if a child cannot leave the room, that room can become anything at all—a forest, a castle, a racetrack,” agrees Antes. “A chair can become a jet plane. Anything can become anything.”

England doesn’t rely on a repertoire of practiced jokes or stand-up shtick. She prefers to make up humor as she goes, customizing it for each child. “One thing I learned at Second City is how to read your audience,” she says. “You could use the same jokes every night, and maybe last night it was super funny and all the jokes hit, but tonight it’s not. In clinical psychology, that’s called attending to the patient, which is essentially the same thing.”

For example, England spontaneously started singing karaoke-style with a little girl who was undergoing a chest-clearing procedure as part of her treatment for cystic fibrosis, a disease that causes mucus to build up in the lungs. The vibrations of the machine caused the child’s voice to waver, and when England copied the vibrating voice in a hilarious way, the child erupted in giggles.

Another girl, who cried inconsolably on her birthday because her mother had to work, rebuffed nurses’ attempts to cheer her. England took a non-threatening approach, making faces and silly motions as she peeked in and out of the doorway until the girl laughed and invited England to enter.

“When you can laugh over something together, it really allows for a deeper connection,” England says. “They say laughter is the best medicine. It’s not like we’re poking fun at what these kids are dealing with—in a way it helps them take their mind off of what they’re dealing with. These are moments when they can lighten up.”